15 May STATSports White Paper – Player Proximity Report

Introduction

As of March 13th, 2020, all professional football matches in the UK have been suspended due to the continued spread of COVID-19.

The cessation of sporting activities at an almost global level has had a profound effect on the footballing calendar, with the 2020 European Championships already postponed to the summer of 2021.

Football authorities have been left with the difficult decision on determining how to resolve the current campaign; some domestic competitions having been declared void, while others have committed to resuming the current season once it is safe to do so.

The latest proposals for a return to football in the English Premier League is a resumption of team-based training on May 18th, with competitive matches beginning on June 8th.

The current guidelines from the UK government regarding social distancing are to remain two metres away from other people at all times [1].

Specific to the resumption of sport, the government have recently introduced a two-step programme for a return to sport.

Step one is described as a return to organised individual training for individuals or groups of athletes, in a defined performance facility while adhering to social distancing guidelines.

Step two will then allow for a level of social clustering and activities such as tackling in team sports, sparring in combat sports and the sharing of equipment [2].

Limited data is available on the proximity of athletes during specific team-based football training activities.

This report aims to highlight the frequency and duration of player incursions within two metres in team-based football training sessions pre COVID-19 where social distancing measures were not applied, in relation to the types of activities performed and number of athletes in the training group.

The report aims to inform practitioners in football on the risk of incursions in group training sessions, which may aid guidance for implementing a safe return to training for athletes and staff.

Methodology

Data was provided by 4 English Premier League teams for a total of 11 training sessions completed prior to the introduction of social distancing measures.

Each player was equipped with a STATSports Apex GNSS device as part of their standard daily practice. The validity of the Apex device to quantify athlete movement at varying speeds in team sports has been demonstrated in previous research [3, 4], and is a certified device under the FIFA Quality Performance test reports for EPTS [5].

The data used for analysis accounts for the total time on grass of all players along with drill specific breakdowns and likely includes breaks in activity, such as recovery and water breaks where players may congregate at close proximity.

The co-ordinates of each player’s positioning throughout the session was logged at a frequency of 10Hz. Data was obtained for 75 players across the 4 teams, resulting in 183 session files and over 750 hours of individual player session data.

The raw positioning data (latitude and longitude) was exported to Python Pandas where a custom spatiotemporal analysis was carried out to determine the frequency of players coming into contact at two metres or less, and the duration of these incursions.

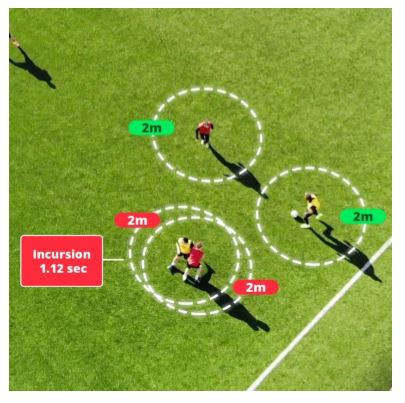

Fig. 1 Depiction of player incursion

Findings/Results

The average session duration was 86.5 minutes across all session analysed with 16.6 players on average active in each session.

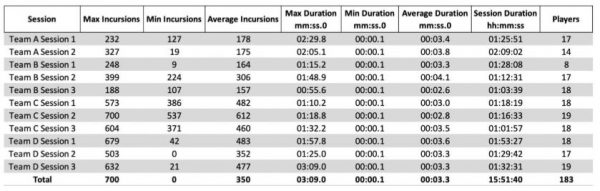

On average, players were exposed to 350 incursions per training session with the average duration per incursion 00:03.3 (mm:ss.0). A summary of all sessions is in Table 1.

Table 1. Summary of incursions per session

Of the observed sessions, Team B Session 1 had the lowest number of participants with 8 Players.

The average number of incursions for this session was 163.5, with an average duration of 3.3 seconds.

The sessions with the largest group of participants, Team C Session 2, and Team D Session 3, both had 19 players involved in the training session. In Team C Session 2 session, there was an average of 612.4 incursions per player with an average duration of 2.8 seconds.

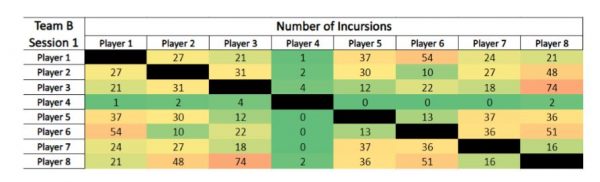

The total number of incursions a player experienced in the smallest and largest group session are illustrated in Tables 2 and 3, respectively.

The matrix highlights the frequency individual players came into contact in each session, with colour-scaling based on the minimum and maximum values observed in both sessions (0-116).

Table 2. Matrix of player incursions for Team B Session 1.

Table 3. Matrix of player incursions for Team C Session 2.

Drill Analysis

An analysis of incursions in specific drills offered a further insight into the activity types which were associated with a higher frequency of player contacts.

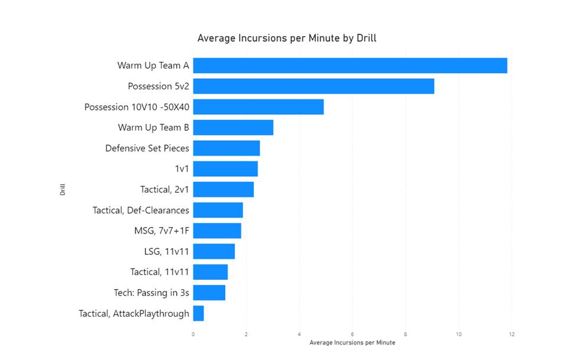

Figure 2 illustrates the average frequency of incursions per minute in the various drills observed.

Team warm-ups and possession-based drills produced the highest frequency of incursions, while large-sided games (LSG), medium-sized games (MSG), and small group technical drills all produced less than 2 incursions per minute.

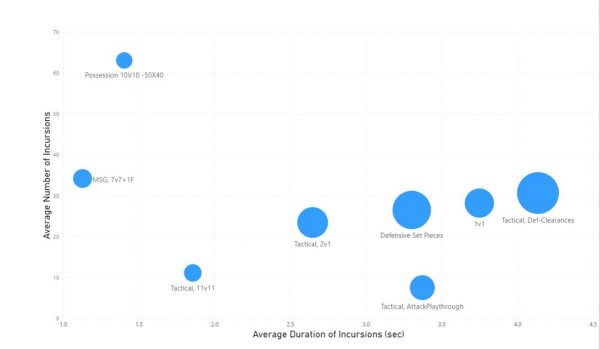

The frequency and average duration of incursions are highlighted in Figure 3, with set-plays and 1v1s showing the largest contact in terms of duration.

Figure 2 . Average number of incursions per minute by drill

Figure 3. Average number and duration of incursions by drill, with max duration indicated by density

Discussion

Unsurprisingly, team-based training activities sees players frequently come into contact at 2 metres or less.

However, these incursion periods are typically brief in duration, averaging just over 3 seconds per incursion, with the majority of player incursions lasting less than 1 second.

As the data collected for this analysis was prior to the implementation of strict social distancing guidelines, it is likely that some incursions occurred during rest periods or water breaks and may involve social interactions.

Video observations would possibly aid future analysis in determining what is ‘effective training time’, which may portray a more accurate representation of incursion time in team-based training activities adhering to specific safety guidelines.

The number of participants had a clear impact on the frequency of incursions as demonstrated in Tables 2 and 3, with players less likely to come into close contact when training in smaller groups.

As such, practitioners may consider running team-based training sessions in smaller groups to best adhere to social distancing guidelines.

As would be expected, the type of drills performed also has a strong influence on the frequency of incursions.

Warm-up activities in the observed sessions recorded a high rate of incursions per minute. This would suggest that practitioners should alter their typical warm up activities when returning to training to reduce the likelihood of players clustering together.

LSG/11v11 drills showed a comparatively lower frequency of incursions than possession-based drills on playing areas with smaller dimensions.

It is worth noting however that while displaying a high frequency of incursions, possession drills typically consisted of brief contact periods of 1 second or less.

Set-plays and 1v1s saw higher durations of incursions compared with other activities. As such, coaches should consider alternatives to these activities while implementing training programmes following social distancing guidelines.

Conclusion

Currently there is limited research available on player proximity during team-based football training sessions.

With the most important aspect of a return to training the health and wellbeing of all associated personal within a team-based setup this exploratory analysis provides information which may be of benefit to football authorities, medical professionals, clubs and their staff in their pursuit of a return to team-based training activities, in a safe socially distanced manner.

The insights provided on how the number of players within a training group and the specific drills carried out effect the number of incursions offers practitioners insight into how training can be modified to ensure they maintain social distance.

References

- GOV.UK, Coronavirus (COVID-19): what you need to do, [online], available: https://www.gov.uk/coronavirus.

- GOV.UK, Elite sport return to training guidance: Step One, [online], available: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/coronavirus-covid-19-guidance-on-phased-return-of-sport-and-recreation/elite-sport-return-to-training-guidance-step-one–2

- Beato, M., Coratella, G., Stiff, A., & Dello Iacono, A. (2018). The validity and between-unit variability of GNSS units (STATSports Apex 10 and 18 Hz) for measuring distance and peak speed in team sports, Frontiers in Physiology, 9, 1288.

- Taberner, M., O’Keefe, J., Flower, D. and Carling, C. (2019) Interchangeability of position tracking technologies; can we merge the data?, Science and Medicine in Football, doi: 10.1080/24733938.2019.1634279.

- FIFA (2019), FIFA Quality Performance Reports for EPTS, [online],available: https://football-technology.fifa.com/en/media-tiles/fifa-quality-performance-reports-for-epts/.