08 Apr Maximum Intensity Periods aiding Return to Performance: A Field Hockey Case Study

Introduction:

Often when an athlete gets injured their primary goal is to return to pre-injury levels of competition and return to play (RTP).

Lozano [1] describes the RTP process as ‘the phases through which an injured athlete safely returns to training and competition while protecting their health, decreasing the risk of re-injury, and minimising the time when the athlete is unavailable for competition.’

The nature of the injury determines the duration of the rehabilitation. It is widely agreed that RTP generally follows the control – chaos continuum [2].

However, when it comes to returning to performance (RTPerf) there is limited research given to the individual approach required for each athlete.

RTPerf is defined as the final phase of rehabilitation before returning to competition, when an athlete ensures they can match or exceeded the level of performance they were achieving pre-injury [3].

Research [4] has identified the importance of high-quality, individualised rehabilitation as a critical aspect of the RTPerf process.

A ‘one-size’ fits all approach does not address the variability that exists between injuries, players, competitive demands and response to load.

For example, the physical demands for a field hockey goalkeeper are vastly different to the demands of a centre midfielder with differences in almost every metric. As a result, frequency, duration and goals of rehabilitation need to be tailored for each athlete to ensure RTPerf is as efficient as possible.

A key feature in using Global Positioning Systems with field hockey athletes is the ability to quantify the demands of competitive match play.

Consequently, this allows athletes and medical practitioners to replicate desired load in a controlled rehabilitation setting to maximise performance and minimise rehabilitation time [5].

One of the many ways to ensure an athlete is exposed to peak game demands during the RTPerf phase is through the use of Maximum Intensity Periods on the STATSports Sonra Software.

The Max Intensity Period (MIP) feature in Sonra, gives the end user the ability to extract the maximal output of a selected metric for a predefined time period using moving averages.

By allowing users to define their own time frame it helps eradicate the underestimation of true maximum intensity demands widely reported in literature as a result of the use of fixed drills [6].

This information can then be utilised by medical support staff to ensure the rehabbing athlete is exposed and comfortable meeting match day demands before inclusion in a match day squad.

Analysis Techniques/

Analysing MIP within Sonra is a simple, four-step process:

- Select the session

- Select the player

- Select the drill

- Finally, select the metric you wish to analyse, e.g. Explosive Distance, Sprints or Total Distance

Implementing MIP

During the RTPerf phase, MIP is implemented to ensure rehabbing athletes are able to match, if not improve on their pre-injury match day demands.

The RTPerf phase of rehab usually entails training matches and is the final few weeks before inclusion in a match day squad.

To calculate the deficit/improvement, we take 3 games pre-injury and calculate average 3min MIP for High Speed Running (HSR), Total Distance (TD) and Explosive Distance (Exp D).

For practitioners to agree a player is ready to return to performance we look for a minimal difference (less than 5% [7]). However, we aim to spend the rehab time allowing athletes to improve on pre-injury levels.

We mimic training to continue emphasising aerobic conditioning (heart-rate exertion and time in HR zone 6) while also tracking HSR (>5.5ms−1) and sprinting (>7ms−1) which is incorporated into team training based upon Taberner, Cohen and Allen’s Control to Chaos continuum [2].

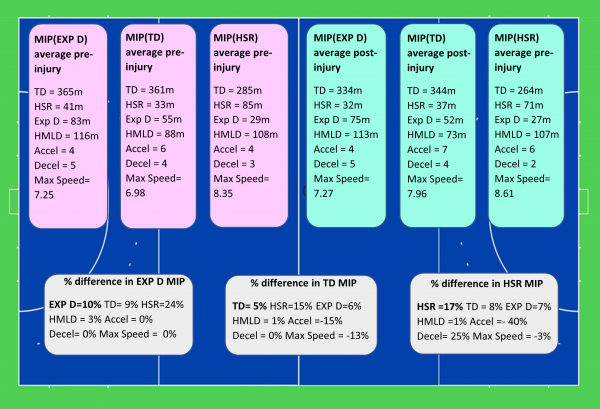

The findings are summarised in figure 1.

Figure 1. highlighting % difference in MIP performance for 3 games, pre and post injury

Statistics and Results

For the injured athlete in question, there are some asymmetries detected, identified as showing positive figures greater than 5% in the percentage difference columns.

This athlete will continue their RTPerf phase of rehabilitation with particular focus on HSR and Total Distance.

Whether this is complete as supplement sprint and running sessions, or whether training is manipulated to include greater HSR, and Total Distance is up to the discretion of the coaching staff (training manipulation may include adapting pitch size, overloading players, or conditioned games).

Once they have returned to pre-injury levels the athlete will remain present during team training and become available for selection as required by team management.

The use of Maximum Intensity Periods highlights how, although an athlete has passed the return to play protocols, they are not yet at pre-injury performance levels.

This process can help to bridge the gap between passing return to play protocols and returning to performance.

Practical Considerations

- MIP calculations can help ensure rehabbing athletes are exposed, and comfortably meeting match day demands before inclusion in a match day squad.

- MIP allows medical practitioners to individualise an athlete’s rehabilitation which can help to improve pre-injury performance levels and minimise rehabilitation time

- A potential limitation: formation/position of the rehabbing athlete was not taken into consideration. [8] highlights how playing formation derived different results in metrics such as Total Distance, High Speed Running, and High Metabolic Load Distance. Consequently, for MIP averages to be useful practitioners will require 3 games pre-injury in the same position and playing formation. The rehabbing athlete will need to continue to play in the same formation and position for post injury MIP figures to be comparable.

- Analysing MIP is a useful tool not only for rehabbing athletes but also for fit athletes. When utilised effectively MIP can be an effective training and drill planning tool as it allows coaches and practitioners to run drills that accurately replicate match demands for the specified drill time.

References

- Lozano, D., Lampre, M., Díez, A., Gonzalo-Skok, O., Jaén-Carrillo, D., Castillo, D. and Arjol, J.L. (2020). Global Positioning System Analysis of Physical Demands in Small and Large-Sided Games with Floaters and Official Matches in the Process of Return to Play in High Level Soccer Players. Sensors, 20(22), p.6605.

- Taberner, M., Allen, T. and Cohen, D.D. (2019). Progressing rehabilitation after injury: consider the ‘control-chaos continuum’. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 53(18), pp. 1132-1136

- Surdyka, N. (2021). Return to Sport Continuum. [online] Physio Network. Available at: https://www.physio-network.com/blog/return-to-sport-dr-nicole-surdyka/ [Accessed 10 March 2021]

- Taberner, M. (2020). Constructing a framework for Return to Sport in elite football (PhD Academy Award). British Journal of Sports Medicine, 54(1), pp. 1176-1177.

- Finlay, S.G., Grelle, B.A. and Andersen, J.C. (2019). Guided load management for female soccer athletes: a case series using global positioning system technology (GPS) during return to sport. International Journal of Sports Physical Therapy, 14(6).

- Brooks, J.H. and Kemp, S.P.T. (2011). Injury-prevention priorities according to playing position in professional rugby union players. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 45(10), pp.765-775.

- Paterno, M.V., Schmitt, L.C., Ford, K.R., Rauh, M.J., Myer, G.D., Huang, B. and Hewett, T.E. (2010). Biomechanical measures during landing and postural stability predict second anterior cruciate ligament injury after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction and return to sport. The American Journal of Sports Medicine, 38(10), pp.1968-1978.

- Tierney, P.J., Young, A., Clarke, N.D. and Duncan, M.J. (2016). Match play demands of 11 versus 11 professional football using Global Positioning System tracking: Variations across common playing formations. Human Movement Science, 49, pp.1-8.

Author Details

Ruth Montgomery

Sport Scientist